Patty Carroll: Domestic Demise

January 10th, 2021

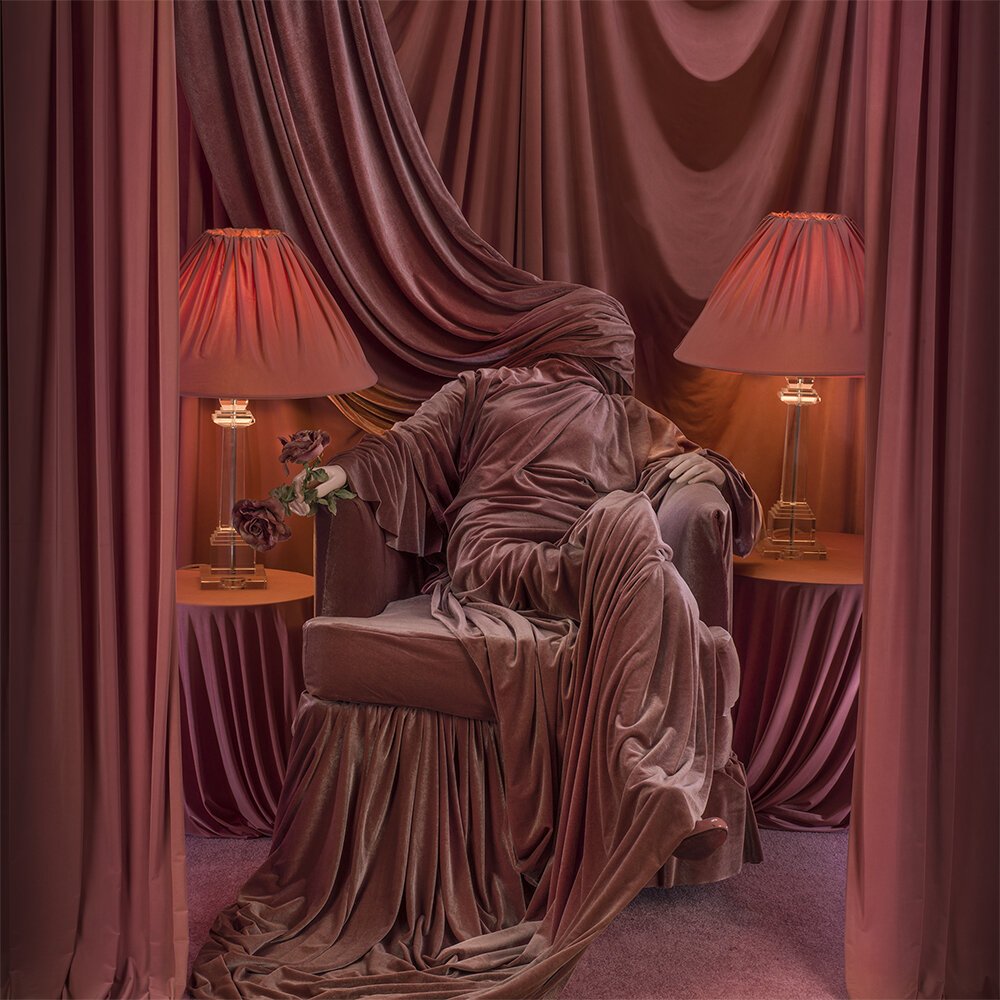

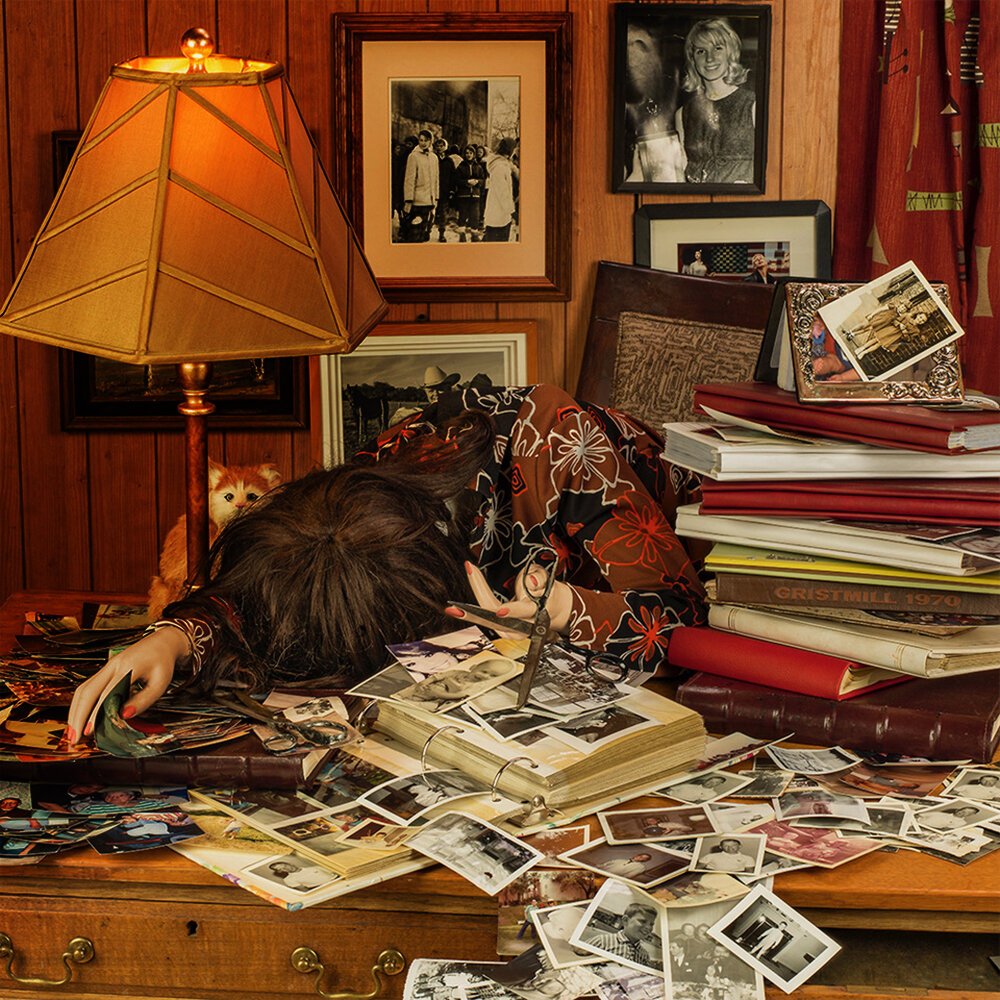

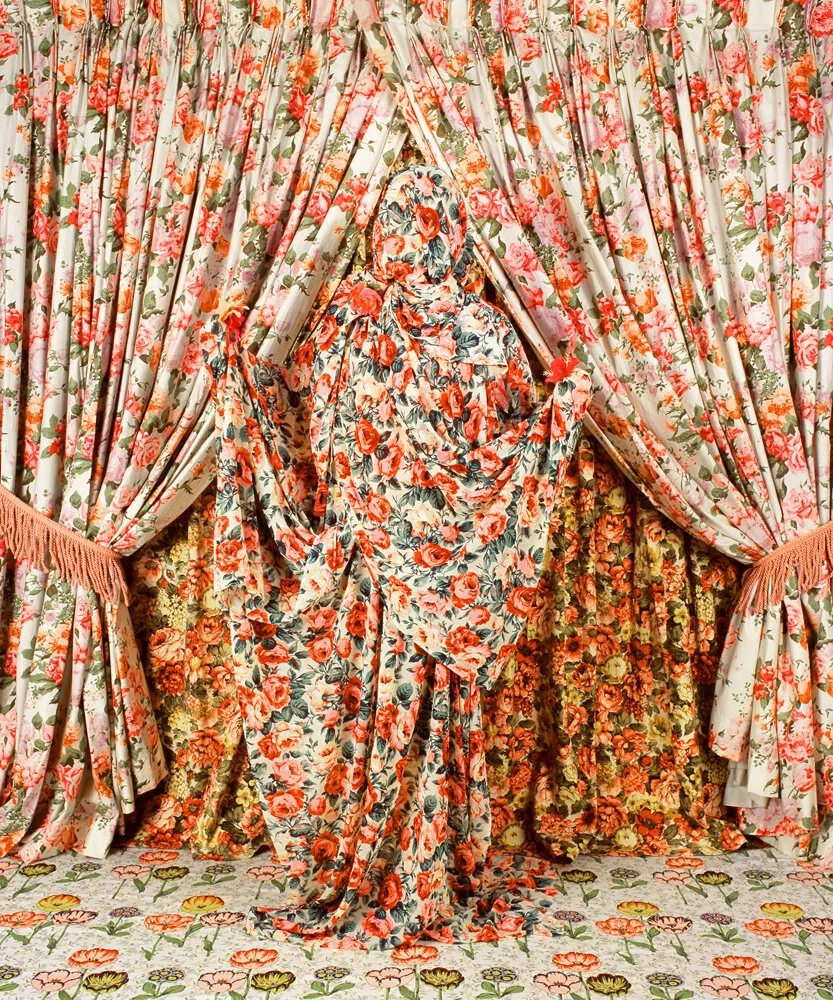

Filled with a macabre humour, the work of photographer Patty Carroll explores the often fraught relationship between women and domesticity. Creating visually bold compositions of excess, her “unportraits” of anonymous women create emotional landscapes of conspicuous consumption, isolation and confinement. We spoke with Patty to look further into the world of her characters, her inspirations and creating images with personal resonance with the viewer.

POL: First up, can you introduce our readers to yourself and how you would define your work?

PC: My work is a colourful hybrid between reality and fiction. I create full-size studio still life images that mimic rooms in a home, where the woman of the house is overwhelmed in her domestic activities and things.

Anonymous Women: Demise is about merging women and home. The woman is hidden among her domestic objects, activities, and obsessions. The still-life narratives comment on the mania of collecting, accumulating, decorating, and working at home. In the series, the objects take over, and the woman is crushed by her own possessions and activities, leading to disaster and mayhem. My photographs are metaphors for the interior lives of women; how we substitute everyday objects and artifice and turn them into obsessions.

POL: You're best known for your multiple Anonymous Women series. Where did this idea of a woman obfuscated by her domesticity originate?

PC: We moved to London and lived there for 4+ years for my husband’s job. Although I had been known back home as a professional photographer/teacher/person in my own right, no one really knew me that way. I also acutely realised that in more traditional societies, most women are still seen through the lens of their domestic status, for instance as Mrs. So, when everyone kept calling me Mrs. Jones (which I am, but continue to use my maiden name,) I was startled. It led to a small identity crisis, and my response was to photograph a model with objects on her head hiding her eyes and her identity. All of the objects were related to the home. I became obsessed with the idea that women are only seen via their husbands, or domestic position in the world.

POL: We love the phrase “unportraits”, which you use to describe these images. Where did this phrase come from? Why did you choose to focus on woman as a symbol rather than creating someone more particular through your imagery?

PC: I did not want the images to be of a particular person because I felt hidden and not acknowledged for my own self. Many women feel this even if not overtly stated. We are seen through our roles as wife, mother, nurse, teacher, cook etc. In order for others to relate to the imagery, it seemed important that my woman be a symbol for and about others.

In the later, more narrative parts of the series, the woman performs her tasks and appears in the home chaos she has created. I have seen women look at the images and say, “that one is me!” It is important to me that others can related directly to the work, therefore if it was a particular person, it would make it about that person, not any or all of us. The idea of the “unportrait” is that yes she is there, but not about only one specific person.

“I became obsessed with the idea that women are only seen via their husbands, or domestic position in the world.”

POL: These works have very rich internal narrative and character building. What’s your process for world building? When you’re constructing your images do you approach them with an internal story pre-defined or does this come whilst shooting?

PC: It completely varies from picture to picture. Sometimes it is easy to build a picture on an idea, such as a recent one called, World on Her Shoulders. With the pandemic, the election, people confined to home and feeling a lot of anxiety, the idea was floating around everywhere, and I searched out a few globes and needed a large one to rest on her. Other pictures can start from a fabric or a prop. For instance, the picture Red Balls is about trying to keep all of her balls in the air at once, but nevertheless, failing. It started with the fabric which I found in a little store in Miami and fell in love with the pattern and color. When I realised it had all these red circles in it, the idea of balls hit home. None of the pictures are pre-defined. Sometimes I start with a very loose sketch, but often we are making stuff up on the spot, which can be really stressful!

POL: We’ve read that you see your images as loosely inspired by the game Clue, and you can see that in both the domestic setting but also the sometimes quite macabre nature of what your work depicts. How did you begin thinking about this relationship to your work?

PC: The work went from the progression of a single, white torso with an object hiding a face, to the drapery hiding the entire figure, to including objects and collections of things, to the latest part of the series, where the woman is overcome in her domestic life. As I wanted it to appear that her activites and things were killing her off, I thought of the game of Clue because each room might be where the murder takes place with various household weapons. I also read a lot of mystery novels.

Mostly I think that the work is often humorous, and humour usually begins with something dark. In my family, my mother had a great sense of humour, and the only way to get through any of the unfortunate situations we experienced was to laugh and make fun of them. I see life as an endless supply of bizarre and wonderful jokes that are based in relentless sorrow. If my women are in absurd situations in the pictures, then hopefully, viewers will get a chuckle or two from them. I try to make the disasters over the top to emphasise farcical situations.

“ I see life as an endless supply of bizarre and wonderful jokes that are based in relentless sorrow.”

POL: In your work there are echoes of other art forms, from renaissance still life paintings, to Pop Art and vintage movies - where do you draw inspiration from? Do you have any artworks or artists who you look to for inspiration?

PC: I get inspiration from a variety of sources not just other artists. However, my favourite artists are the surrealists and a group of Chicago painters in the 1960s- 70’s that were called the “Hairy Who”. Their style was rich in color and absurd figuration. Also, my favourite movies are old musicals from the 1950's and 60's because of the saturated color in them, and they usually have an imaginary sequence.

I have always loved bright, saturated primary colours, maybe the way a kid does. Colour is emotion, life, and energy. The initial imagery of the head and torso was influenced by white marble statues seen in museums worldwide. Since we were living in Britain, it was easy to travel to other parts of Europe and have the traditional paintings and sculptures make their way into my perview in a more direct way. I also started loving De Chirico then, not just the other surrealists.

POL: Looking across all of your imagery there is a sense of nostalgia evoked, but this nostalgia is often quite pointed. Every work is tinged with an unease, since your images can on the one hand be very glamorous but are yet also imbued with an explicit criticism for the social politics of the past (and present). How do you find a balance between evoking a visually rich sense of time and place without romanticising it?

PC: I am not nostalgic about the past, but rather wish we could live the myths instead of the reality of today or even then, whenever that was! I am trying to both critique and celebrate situations in the imagery. It is a hard line to hold, but I think that is where humour and beauty can help. If an image is visually rich, it is easier to look a bit further into it and digest other meanings. “A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down”.

POL: Your works can be very serious in subject matter and political importance, however there is always a sense of humour in your imagery. Do you think humour can be a powerful tool for inciting progressive change?

PC: I certainly hope so! Sometimes you have to turn things around to get the point across. Ruth Bader Ginsburg argued for gender equality by using the argument that it applied to men as well as women. So sometimes, we have to look at issues from another perspective to actually see the real problem. I think humour provides the opportunity to often see things as they really are.

“I have always loved bright, saturated primary colours, maybe the way a kid does. Colour is emotion, life, and energy.”

POL: There can be a tendency (and we’re sure we’re guilty of it too!) of focusing in on photographic or philosophical theory in works over appreciating the aesthetic beauty of an image. Your works are visually overwhelming but are all balanced and aesthetically stunning. When you’re working are you thinking about theory or are you focused on the aesthetics first?

PC: It has to be a balance and combination of both. If a picture is not exciting or interesting to look at, it doesn’t matter to me what it is about. I think form, color and all aesthetic decisions will enhance our reading of an image. I do not subscribe to the philosophy of having meaning so well hidden in dull imagery that one needs an essay to explain it. On the other hand, it is really important to make sure that there is a message in each image, whether political, personal, or emotional.

“If a picture is not exciting or interesting to look at, it doesn’t matter to me what it is about. I think form, colour and all aesthetic decisions will enhance our reading of an image. I do not subscribe to the philosophy of having meaning so well hidden in dull imagery that one needs an essay to explain it.”

POL: Every one of your images, from still life pieces like Flora and Fauxna to the Anonymous Women works, are compositions of abundance. How do you go about building your sets? Where are you finding your props?

PC: I look for props everywhere. These projects have taught me how to be a smart shopper. I scrounge for stuff in thrift stores, antique malls, sometimes estate sales, online shopping, regular stores, and my assistant is very good at finding things on Craigslist. I also have friends who owned a drapery shop and they would lend me drapes etc. Since they just went out of business, I made a great haul with fabric that they were getting rid of. The point is, the sources for props and material are everywhere. Often it takes a long time to accumulate enough pieces before making the picture. I have a large garage at the back of my studio and it is filled with bins of props and fabric and paint. We also keep some random pieces of furniture around, usually found in thrift stores or in an alley. However, I also get rid of so many things after they are used, but it never seems to even out, because it is really crowded back there now.

Having said all of that, I also have collections of vintage objects that worm their way into my pictures. For instance, the Panther picture was made with some of the panther tv lamps we have collected and live in our basement room. The entire drapery series started when I was furnishing our 1950’s ranch house and looking for vintage objects to complete the décor. My hunting for the house led me to hunting for objects to put into photographs, and it sort of exploded!

“I am trying to both critique and celebrate situations in the imagery. It is a hard line to hold, but I think that is where humour and beauty can help. If an image is visually rich, it is easier to look a bit further into it and digest other meanings.”

The birds in the Flora and Fauxna series started on a lark because I found a couple of ceramic birds in an antique mall, then started finding others. One day, in an open studio day, a woman saw the set up for one of the pictures and said that her mother collects birds. A month later she brought her 85 year-old mother to the studio and after we talked a while, she went to the car and brought me 3 boxes of birds she no longer wanted. This led to me photographing them, taking her the pictures and then she kept giving me more birds! Now I have way too many birds but have made lots of still-life photographs of them. The entire series was based on the idea that birds living in their homes are often heard, but not seen, as they are camouflaged in the trees also. They seemed an apt symbol for my women. I also remember the girls were slangily called “birds” in Britain in the 1960’s.

POL: We imagine it must be difficult to walk away from a set up when you could in theory continually add to them. How do you know when you’ve got a composition just right?

PC: How do you know how much garlic or salt to add to a dish? The process is like tasting! We set up a picture, then look at it on the computer screen, and then adjust things – placement of objects, changing lighting, straightening fabric etc. We usually repeat the process many times until it feels right. Sometimes, we walk away from it overnight and reassess the set-up in the morning for the final tweaks.

POL: If time and money were no object, is there a project you would love to do?

PC: I cannot imagine such a thing!

“The truer you can be to yourself, the more others will relate to your imagery.”

POL: You used to teach photography at a University Level, what one bit of advice do you think all photography students, and emerging photographic artists, should know?

PC: I no longer teach, but I did for 40 years! The best advice I can give people is to know who they are, celebrate it and keep going. We are all unique, but as Diane Arbus said, “The more specific you are, the more general it will be.” In other words, the truer you can be to yourself, the more others will relate to your imagery.

POL: What are you working on now? What’s next?

PC: I am still continuing with my Domestic Demise series. I also want to start a new series of still-life photographs without the figure but haven’t gotten to it yet. I also have made a few installations of household things to accompany the photographs in exhibits and paired them with the drapery pictures. I like working with the actual materials on the wall and creating life-sized vignettes.

Who knows what the future will bring? Who could have predicted this year? I am still just trying to get through it!

About Patty Carroll

Patty Carroll has been known for her use of highly intense, saturated color photographs since the 1970’s. Her most recent project, “Anonymous Women,” consists of a 3-part series of studio installations made for the camera, addressing women and their complicated relationships with domesticity. The photographs were published as a monograph, Anonymous Women, officially released in January, 2017 by Daylight Books, and most recently Anonymous Women: Domestic Demise published in 2020 by Aint-Bad Books.

The Anonymous Woman series has been exhibited internationally and has won multiple awards including Carroll being acknowledged as one of Photolucida’s “Top 50” in 2104 and 2017. Her work has been featured in prestigious blogs and international magazines such as the Huffington Post, The Cut, Ain’t Bad Magazine, and BJP in Britain. Her work has been shown internationally in many one-person exhibits in China and Europe, as well as the USA. (White Box Museum, Beijing, Art Institute of Chicago, Royal Photographic Society, Bath, England, among others.) She has participated in over 100 group exhibitions nationally and internationally, and her work is included in many public and private collections. After teaching photography for many years, Carroll has enthusiastically returned to the studio in order to delight viewers with her playful critique of home and excess.